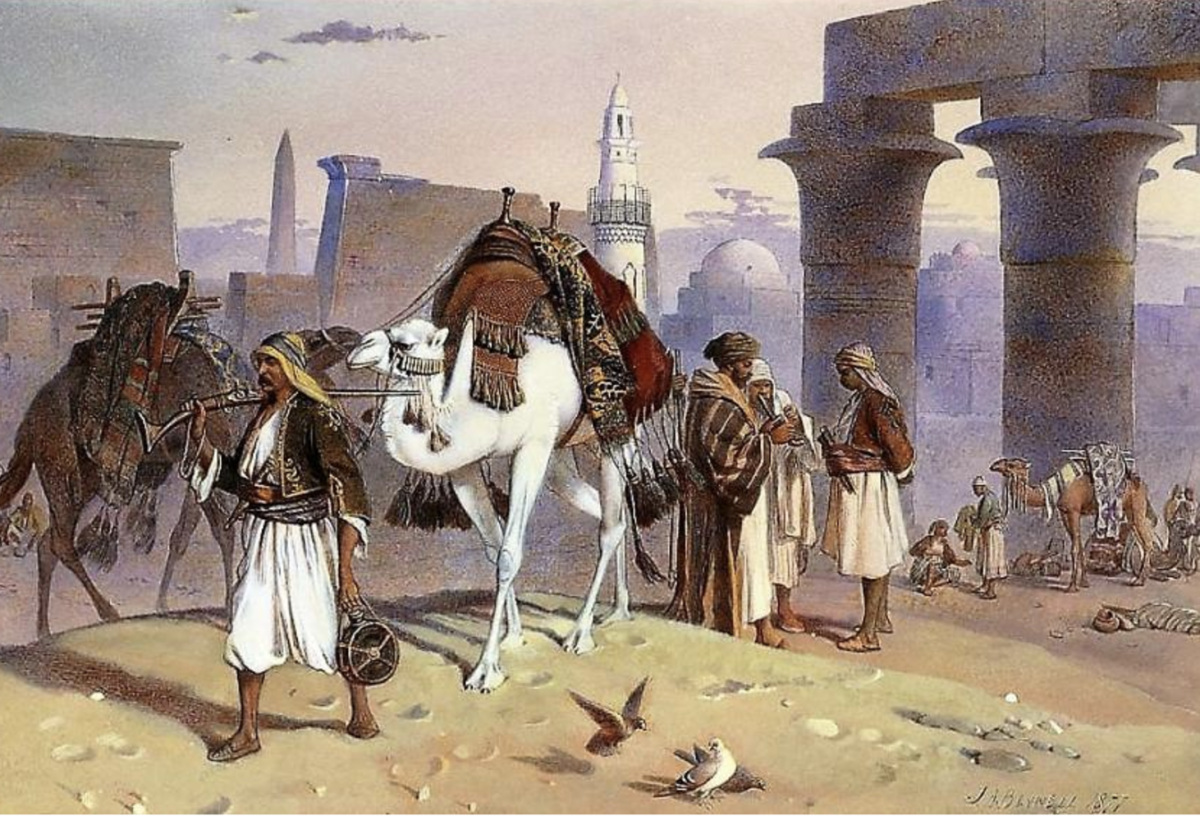

‘Travellers at Luxor’, 1877 – Joseph Austin Bentwell

In 1877, German photographer and traveler Ferdinand von Richthofen coined the term the “Silk Road” to describe the almost 6437 kilometers (or 4000 miles, for all you Americans out there) caravan routes that were once sprawled from China all the way to Europe. These interconnected trade routes had been used from when the Han Dynasty of China opened to trade in 130 B.C.E. until 1453 C.E. when the Ottoman Empire closed off trade with the West and had a massive impact on how we live our lives today.

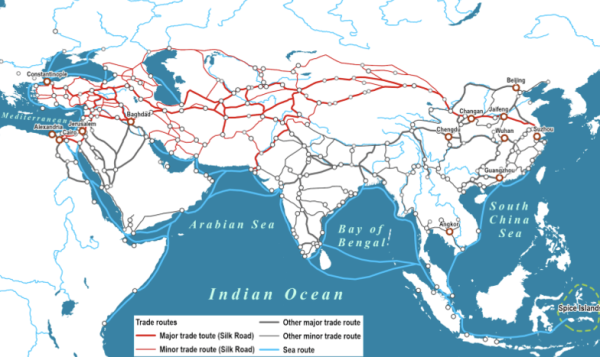

Trade network adapted from Martin Jan Mansson – The Geography of Transport Systems

The Silk Road was a network of trade routes that involved two main courses: one from the Eastern Mediterranean to Central Asia and the other from Central Asia to China. It also included its fair share of sea routes and was surprisingly the most enduring trade system throughout human history despite its reputation for being a common place to find robbers. Because of this, merchants would often group together to form caravans, which resulted in the construction of many caravanserais and towns along the way. However, the Silk Road didn’t just physically impact our world; it also transferred powerful ideas across the harsh terrain that would have an even grander impact on our lives. But to truly understand the scope of its implications, let’s step back and start from the beginning.

The Persian Royal Road:

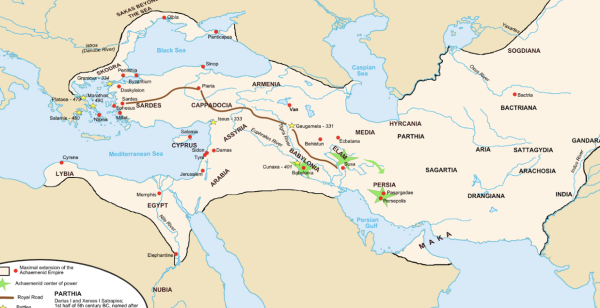

Persian Royal Road (Illustration) – World History Encyclopedia

Under Darius I, the Persian Empire founded the Royal Road, a massive trade route around half the size of the soon-to-be Silk Road, in 500 B.C.E., stretching from Susa in modern-day Iran to Sardis in modern-day Türkiye. They also formed many more minor routes that reached parts of the Indian subcontinent and northern Africa as well, and the network “went on to serve as an integral link in the Silk Road, according to UNESCO. Not only that, but the writings about its messengers would soon inspire the United States Postal Creed.

The Han Dynasty and the Xiongnu Dilemma:

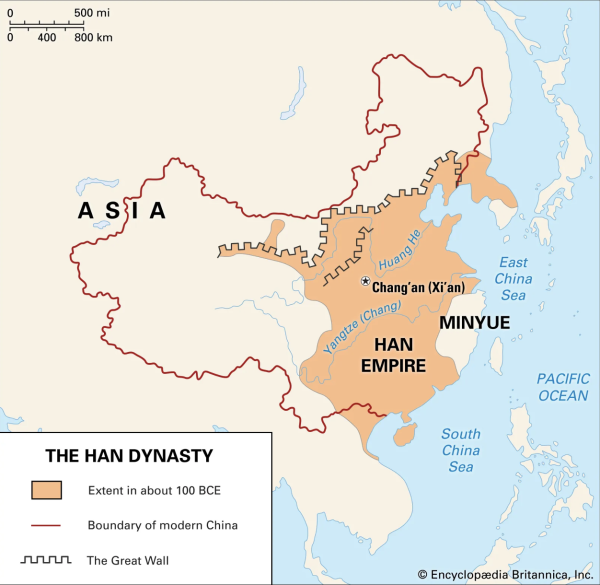

Map showing the extent of the Han empire c. 100 B.C.E. – Britannica

About 300 years later, in the second century B.C.E., Emperor Wu of the Han Dynasty faced a problem. He had to solve the Xiongnu threat to the north but did not have any idea as to how he could do that. He sent Zhang Qian, a Chinese explorer, to seek help from the Yuezhi, an ancient people who ruled Central Asia. On the way, Qian was introduced to many new groups and cultures, particularly taking an interest in the Dayuan, their horses, which were much more powerful than those bred in China. When he returned to China, he told Wu about them, and the emperor decided to purchase them. In a short period, they were finally able to deal with the Xiongnu threat. Inspired by his victory, Emperor Wu decided to continue this collaboration between peoples and opened the Silk Road in 130 B.C.E.

Silk Is a Big Deal!

Women Checking Silk, Song China (unknown artist) – World History Encyclopedia

Silk was first developed in China sometime between 6000 and 3000 B.C.E. and went from being a luxury only attained by royalty to a material used throughout Chinese culture. For ages, silk was only produced in China, and its production process was shrouded in secrecy. It was used by the Chinese as fishing lines, to satisfy nomadic raiders and was exported (usually as clothes), making up most of China’s wealth at the time, so it’s no surprise that it was a pretty big deal on the Silk Road (hence the name). Even though it could not be afforded by most, it had a massive impact on the economies and societies of Afro-Eurasia because so many people became involved in its production.

Of course, the Silk Road did not just involve trading silk. China also exported raw materials. The Mediterranean was known for other goods like oil and wine, India for its fine cotton textiles, East Africa for its ivory, and Arabia for its incense and tortoise shells.

The Nomads of Central Asia

The nomadic peoples of Central Asia were also crucial to the Silk Road’s development. Most of Central Asia isn’t exactly suitable for farming, with its harsh conditions and terrain, but that made it difficult to conquer (apparently not for the Mongols, though, but that’s for another time). Because of their frequent traveling, they were more immune to disease and were great traders, and as a result, ended up founding many cities. These cities continued to grow as most of the travel on the Silk Road was done by caravans (due to how common it was to get robbed), who had to stop frequently for supplies.

The Spread of Ideas

It is important to note that the Silk Road wasn’t just known for its trade of goods and materials—it was also known for its trade of ideas. For example, it was the primary road for the spread of Buddhism and Christianity to China. This exchange of ideas made way for new technological innovations that would forever leave their mark on our world.

The Black Death

The Triumph of Death, Pieter Bruegel the Elder 1562

With the gradual loss of Roman territory in Asia and the rise of Arabian power in the Levant, the Silk Road became increasingly unsafe and untravelled. However, it was revived under the rise of the Mongols in the 13th and 14th centuries and is believed to have been a critical factor in the spread of one of, if not the deadliest pandemic in human history- the inevitable Black Death, killing 30 to 50 percent of the entire European population, and 72 to 100 percent of anyone who comes in contact with it without modern antibiotics.

Where Is the Silk Road Today?

After the Ottoman Empire conquered Byzantium, it cut off virtually all trade with the West and shut down the Silk Road. As a result, Europeans began exploring the seas instead, marking the beginning of the Age of Discovery (and European colonialism).

A chunk of the Silk Road still exists today as a paved highway connecting Pakistan and the Uygur region of Xinjiang, China. It has been a driving force behind a United Nations trans-Asian highway, and the UN Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific (UNESCAP) has proposed a railway version.

Overall, although nowhere near as great as it used to be, the legacy of the Silk Road lives on. It continues to be seen through its effects on our economy, the technologies we use, the spread of ideas, and the foundations of globalisation. Ultimately, it highlights how beneficial cross-cultural exchange and cooperation can be and how historical events are amazingly dependent on one another.

References:

- Britannica (2021). Silk Road | Facts, History, & Map. In: Encyclopædia Britannica. [online] Available at: https://www.britannica.com/topic/Silk-Road-trade-route.

- National Geographic Society (2022). The Silk Road. [online] education.nationalgeographic.org. Available at: https://education.nationalgeographic.org/resource/silk-road/.

- The Geography of Transport Systems. (n.d.). The Silk Road and Arab Sea Routes (11th and 12th Centuries) | The Geography of Transport Systems. [online] Available at: https://transportgeography.org/contents/chapter1/emergence-of-mechanized-transportation-systems/silk-road-arab-sea-routes-12th-century/.

- en.unesco.org. (n.d.). The Diary of Young Explorers: Iran and the Royal Road | Silk Roads Programme. [online] Available at: https://en.unesco.org/silkroad/content/diary-young-explorers-iran-and-royal-road.

- The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica (2019). Zhang Qian | Chinese explorer | Britannica. In: Encyclopædia Britannica. [online] Available at: https://www.britannica.com/biography/Zhang-Qian.

- The Editors of Encyclopedia Britannica (2016). Yuezhi | ancient people. In: Encyclopædia Britannica. [online] Available at: https://www.britannica.com/topic/Yuezhi.

- Unrv.com. (2019). Silk in the Roman Empire | UNRV.com. [online] Available at: https://www.unrv.com/economy/silk.php.

- Shipman, P. (2018). The Bright Side of the Black Death. [online] American Scientist. Available at: https://www.americanscientist.org/article/the-bright-side-of-the-black-death.

- en.wikivoyage.org. (n.d.). Age of Discovery – Travel guide at Wikivoyage. [online] Available at: https://en.wikivoyage.org/wiki/Age_of_Discovery.

- josephaustinbenwell.yolasite.com. (n.d.). Joseph Austin Benwell Artwork Biography, Orientalist Art Movement. [online] Available at: https://josephaustinbenwell.yolasite.com/orientalist-paintings.php.

- Fabienkhan (2016). Persian Royal Road. [online] World History Encyclopedia. Available at: https://www.worldhistory.org/image/5515/persian-royal-road/.

- The Editors of Encyclopedia Britannica (2018). Han dynasty | Definition, Map, Culture, Art, & Facts. In: Encyclopædia Britannica. [online] Available at: https://www.britannica.com/topic/Han-dynasty.

- World History Encyclopedia. (2017). Women Checking Silk, Song China. [online] Available at: https://www.worldhistory.org/image/6920/women-checking-silk-song-china/.

- Brooke, J. (2020). The Black Death, Globalization, and Our World Today. [online] origins.osu.edu. Available at: https://origins.osu.edu/connecting-history/covid-black-death-plague-lessons.

- CrashCourse (2012). The Silk Road and Ancient Trade: Crash Course World History #9. YouTube. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vfe-eNq-Qyg.

- Knowledgia (2022). How Did the Silk Road Actually Work? [online] www.youtube.com. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=J-pfeFbssMw.