There was a joke where Hungarian Regent Admiral Miklós Horthy was asked by Benito Mussolini why the Kingdom of Hungary had an Admiral despite being a landlocked nation. It’s said in this joke that Horthy replied “Why does Italy still have a finance minister?”

The Kingdom of Italy in WWII

Map of Italy 1924 [1]

The Kingdom of Italy joined the Second World War in 1940. It had joined for a string of reasons ranging from ideological ones in a hope for a revival in the glory of the Roman Empire, to political ones, such as the lack of the promised lands for its role in the First World War.

The kingdom enjoyed some successes prior to joining the war, including the occupation of Albania in 1939 and the success in defeating Ethiopia in 1937 (though a guerilla war continued).

After joining the war, Italy was successful in the occupation of British Somaliland and saw early successes in East Africa. In North Africa, with the help of Erwin Rommel (Ger.) and the Afrika Korps, the Italians occupied much of Northern Egypt (Brit.) before the defeat at El-Alamein brought this to a close. The occupation of Corsica with Case Anton, and the occupation of Greece after a brutal campaign saw more land added to the Italian Empire.

Of course, this series of gains would not last, and Italy surrendered in 1943 following the Italian Campaign and the invasion of Sicily and Southern Italy (and collapse of the Italian overseas territories), which lead to a brutal civil war that lasted until the end of the war in 1945.

While the series of hits and misses that was the Italian involvement in the Second World War earned the country the nickname as Europe’s soft underbelly, there is no denying that as one of the main axis powers, Italian involvement cannot be overlooked.

Economics of Fascist Italy

Data

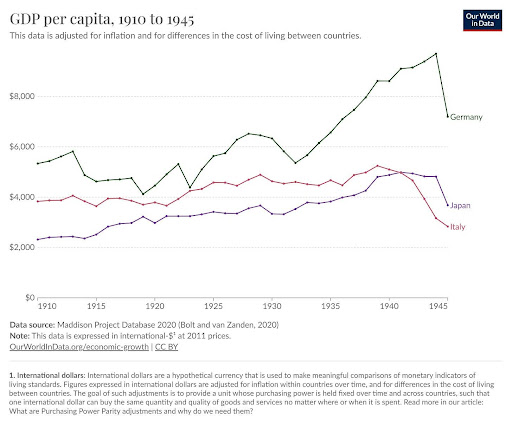

The graph above displays the real GDP per capita of Italy compared to the other main axis powers, Germany and Japan. Notice that Germany in general has the highest GDP per capita (with some falls around the 1920s). Japan generally had lower GDP per capita, until the 1940s where it began to overtake Italy.

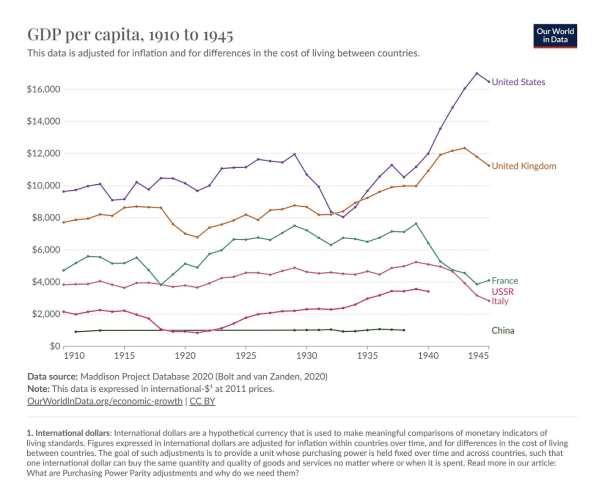

Above is a different graph comparing the GDP per capita of Italy with the other Great Powers, whom it fought against in World War Two. Post 1940s United States is significantly higher than the nations as wartime production rises dramatically.

Italy was often referred to as a second-rate power, if not regional power, as a result of its lack of economic development and a lower standard of living compared to other Great Powers.

There is no evidence that Italy’s standard of living, which is the lowest of the major powers, has been raised one jot or tittle since Il Duce came to power. – Life Magazine 1938

1918 to the The Great Depression

Italy left WWI as a victorious power. It had joined the war against the Central Powers in hopes of gaining back old territories controlled by the Ancient Republic of Venice, which had by this point been controlled by the Habsburg Austro-Hungarian Empire.

Italy had fought on the front against Austria-Hungary in the war, in the areas of Northern Italy. The campaign had, in the end, been a victorious one though it came at a heavy cost to both sides. The front had stalled to trench warfare, but at very high altitudes in the mountains, and with extremely cold weather.

Failed offensives, such as the 12 battles of Isonzo (yes, there were 12) had brought huge human casualties to the country, though in the end with the decisive victories at Vittorio-Veneto and the 2nd Battle of the Piave river brought Austria to collapse.

The Italians had received new territory from Austria for its efforts, though entered the inter-war period with massive debts, inflation and economic depression. The war was a victory, but also a defeat to the Kingdom.

By the 1920s, there had been food shortages, unemployment and strikes.

The PNF (Partito Nazionale Fascista) came to power in Italy in 1922 following Mussolini’s infamous March on Rome.

The reign of the PNF began in a period of instability as a minority government. The first few years saw a liberal economy under Alberto De Stefani as minister of finance, the leader of the centrist party.

Taxes were repealed and state monopolies on life insurance were privatised. There had been an emphasis on productivism, where economic growth was a means of social regeneration. Until 1925, the economy grew through inflation. De Stefani was fired and the government became more involved in the economy as their power became secure. Lending to the private sector increased at 23.8% annually, and joint-stock banks net profits doubled.

The lira declined in 1926. Though this made Italian exports more competitive in foreign markets, it was disliked by Mussolini. He sought to restore it to the original exchange rate, and so Italy went through a period of deflation, as well as rejoining the gold standard. Monetary and fiscal policy in the form of reducing money supply and increasing interest rates furthered this plan, though this did produce a recession as a result.

The policy of Italy moved further towards the side of interventionism, with a focus on corporatism, with large interest groups in control. Many fascist industries and unions formed the Pact of the Vidoni Palace (c. 1925). By this point, the bureaucracy was huge, and syndicates had considerable power. The government assured the populace that all associations would become a larger corporate state.

From 1927, the country moved towards a corporative phase, and emphasised the importance of private initiative for economic organisation. However, government intervention was still a reserved right, which included the fascist control over hiring, which created a sprawling bureaucracy in its own right.

Cartels in the economy increased, with support from government intervention. Cartelisation resulted in an undermining of many government formed organisations for industrial cooperation however, though cartels were able to continue this by maintaining pro-fascist policies.

The Battle of the Grain also happened at this time, where the government intervened to help domestic growers and increased taxes to stop some imports. This reduced competition, though it caused inefficiencies. In the end, it is argued by historians to be a propaganda victory, with an economic defeat and expense instead.

In the early 1930s, the Great Depression hit Italy. The government intervened on the side of banks, though the bail-out was largely illusionary. The assets were largely worthless, and the financial crisis of 1932 occurred. Italian banks collapsed, brought more state intervention to reimburse banks, and lent to private industry/

The IRI was also formed to take control of industries formerly owned by banks, and most of the economy was under the control of the state.

The economic policies during this time led to the state having power over production and allocation of resources, and by 1939 Italy had the highest rate of state ownership of an economy in the world, apart from the USSR. The IRI was effective in its duties, and was instrumental in post-war economic development.

Post-Depression, Autarky and Rearmament

Following the Great Depression, there was a shift in economic policy to match its foreign ones. There was a push for Autarky (or self-sufficiency) following the trade embargoes as a result of the invasion of Abyssinia (c. 1935). Resources had become inefficient and expensive to buy from foreign suppliers, and so there was a push for independence from foreign imports.

From 1929-1939, the economy grew by 16%, but this was only half the level of the period of a more liberal economy from earlier years. Agriculture was still the centrepiece and main sector of the Italian economy, despite the push towards industry. Employment grew only 4% between 1921-36 and modern industries experienced little growth.

Attempts at modernising the agrarian sector also failed, as land reclamation and focus on grain production was arguably inefficient and more rewarding crops were not supported as much. It is said that rural poverty and insecurity rose.

By the late 1930s on the eve of war, the economy was not able to sustain the demands for Italy’s militarism. Raw material production was limited and equipment was low in quantity and quality. 10% of the GDP was directed towards the armed forces, there was a lack of stockpiling for the war, mostly due to commitments to the Spanish Civil War and the Italo-Albanian War.

The War

The war was disastrous for Italy economically. We now know that it went in relatively underprepared. Compared to the other Great Powers, the industrial might of Italy was still that of a power, but nowhere near the ability to be able to wage a prolonged war without serious damage.

During the war, the production and transport infrastructure was heavily damaged from fighting and aerial attacks. GDP per capita had fallen and consumption collapsed. Foodstuffs was scarce from the blockade and fall in production and the ineffective rationing (failing to distribute food of high enough quality) made this worse. Inflation rate was also very high.

It is said that due to the bombing, 12.5% of the Northern industry, 38.5% in the Centre, 35% in the South and 12% on the islands surrounding the peninsula were damaged. From 1940-1945, livestock production diminished by 55%, and the grain production halved. Severe drought post 1942 led to a food shortage and average calorie intake fell by around 2000 calories.

Finally, the loss of human lives during the war was substantial, and around 457,000 deaths were reported, civilian and military, leading to a fall in productive potential.

Post War

US Army in Rome, Circa. 1945. Ph. Public Domain on Wikipedia

“the lira fell to a thirthieth of its value“ – Bank of Italy

In January 1945, Luigi Einaudi was installed as Governor of the Bank of Italy. He laid the groundwork for a return to normality for post-war reconstruction.

The economy was demobilised and reconverted to a civillian one. Luckily, this did not cause much instability for banks, as the reforms of 1936 prevented substantial illiquid assets possession by banks.

Unfortunately, the situation of Italy’s lira was more concerning, and inflation became a larger issue at hand.

Monetary stability was achieved in the period of 1945-1948 through the 4 essential points, which the Bank of Italy described as:

- Halting inflation.

- Re-establishment of a limit to the monetary financing of the state.

- Joining the international financial community.

- Reorganisation of banking supervision.

Protection of savings was added to the constitution of 1948, and the strengthening of the lira laid the groundwork for non-inflationary growth.

Italy’s receival of international aid from the Marshall Plan, Interim Aid and the World bank brought it out of its financial emergency and began post-war reconstruction into the late 1900s.

Further reading and references:

- [1] – By Gigillo83 – Own work, original from Derivative works of this file: Kingdom of Italy 1919 map.svg, CC BY 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=15583585

- https://www.elsevier.es/es-revista-investigaciones-historia-economica-economic-328-articulo-the-impact-world-war-ii-S1698698917300759#:~:text=During%20WWII%2C%20Italy%20suffered%20notable,pre%2Dwar%20levels%20around%201950.

- https://www.nationalww2museum.org/students-teachers/student-resources/research-starters/research-starters-worldwide-deaths-world-war

- https://www.bancaditalia.it/chi-siamo/storia/seconda-guerra-mondiale/index.html?com.dotmarketing.htmlpage.language=1&dotcache=refresh

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Economy_of_fascist_Italy#After_Depression

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Italian_front_(World_War_I)