An orca in a cramped, scorching pool repeatedly rams her head into the metal gate that prevents her from escaping. Another is snatched from the wild after witnessing her mother being harpooned. Yet another suffers from failing kidneys and near blindness, having lived in captivity since 1969.

While they may appear dramatic, these are the true stories of Kiska, Shamu, and Corky, orcas held captive in aquariums. Kiska was captured from the wild in 1979 when she was about 3 years old. She never saw the wild again, dying in captivity in 2023 due to a bacterial infection. Shamu lived from around 1961 to 1971, just one-fifth the typical lifespan of a wild female orca. Corky was taken from the wild in 1969. As of 2025, she is still living in captivity. She had seven calves that lived no longer than 46 days and suffered 3 miscarriages. Captive orcas should not be captured from the wild and bred in aquariums, as they are mistreated, forced to breed, separated from their families, and live much shorter lives than wild orcas.

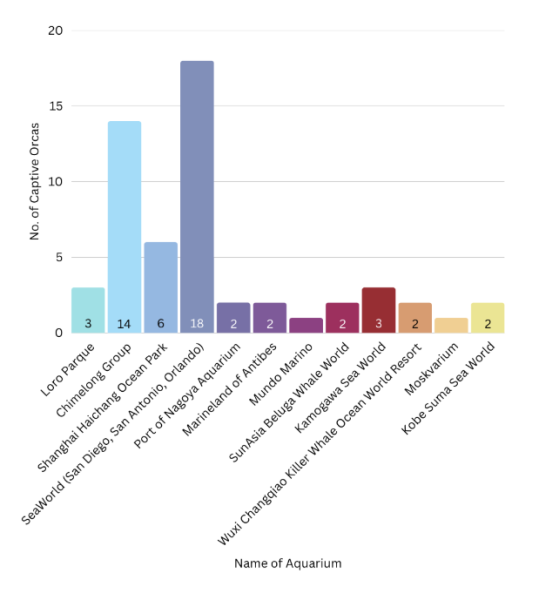

At least 166 orcas have been seized from the wild since 1961, and 133 of those orcas are now dead. Currently, there are around 55 captive orcas around the world, and it is only a matter of time before they die in captivity, never to see the wild again. Many aquariums train the orcas and use them for shows, and sometimes even deprive the orcas of food in order to train them. This chart shows the locations of the orcas currently in captivity.

Captive orcas live much shorter lives than wild orcas, and they even begin to manifest unusual behaviour, such as biting and repeatedly swimming around in circles. In addition, it’s very evident that captivity compromises orcas’ health, especially in their teeth and skin. It’s basic biology. A captive-born orca that has never lived in the ocean still has the same innate drives.

“If you have evolved to move great distances to look for food and mates then you are adapted to that type of movement, whether you’re a polar bear or an elephant or an orca,” says Naomi Rose, a marine mammal scientist at the Animal Welfare Institute, a nonprofit organization based in Washington, D.C. “You put orcas in a box that is 150 feet long by 90 feet wide by 30 feet deep and you’re basically turning them into a couch potato.”

SeaWorld made the decision to end their orca breeding program in 2016. While no more orcas will be bred in captivity by SeaWorld, the Chimelong Group has started a new breeding program for their orcas. As of March 2025, Chimelong holds 14 orcas, 9 of them captured from the wild and 5 born in captivity. According to Taison Chang, chairman of the Hong Kong Dolphin Conservation Society, breeding orcas in captivity could have serious negative effects. The orcas at Chimelong could be family, as they were captured from the same habitats in Russia. “If they’re related, sooner or later they’ll find some genetic diseases in the orcas because they’ll keep inbreeding,” says Chang.

In addition to the poor conditions the orcas live in and the breeding programs at aquariums, SeaWorld has been reported to have separated mothers from their calves at an early age. In an interview with John Hargrove on the separation of mothers and calves, a former SeaWorld trainer who wrote Beneath The Surface, Hargrove says, “This is one of the most infuriating things to me because I can tell you — my own personal knowledge, [so] this is a conservative number — I know of 19 calves we have taken from their mothers. … This is where SeaWorld tries to be clever and tries to get people with semantics. What they’ve tried to do is redefine the word “calf” by saying a calf is no longer a calf once they’re not nursing with their mother anymore, and that’s simply not true. A calf is always a calf. For example, Kasatka and Takara, when they were separated when Takara was 12, Takara is still Kasatka’s calf, and they would remain together for life in the wild. … SeaWorld has separated mothers from their calves before they had stopped nursing. They took Keet away from Kalina, and he was only 20 months old, and he was still nursing.”

Overall, it is clear that orcas do not do well in captivity, and using these majestic wild creatures for human entertainment is not only bad for their health but also dangerous for the trainers involved. Ways to partially release orcas that have lived in aquariums for long periods of time are being considered, such as seaside sanctuaries. However, releasing these orcas is very controversial, as they may not be able to adapt to the wild after living in captivity for so long. Orcas are endangered in the wild; however, breeding them in captivity is not the solution, as returning them to the wild may not be successful. In addition, these captive-born orcas are likely to be used by the aquariums for shows. While we may not be able to successfully release the orcas currently in captivity, breeding them will only do more harm than good.

Sources:

- https://savedolphins.eii.org/news/the-sad-death-of-kiska-the-worlds-loneliest-orca

- https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/2023/09/22/how-long-do-orcas-live/70660108007/

- https://www.worldanimalprotection.us/latest/blogs/how-kiska-became-loneliest-whale-world/

- https://us.whales.org/our-goals/end-captivity/orca-captivity/

- https://www.nationalgeographic.com/animals/article/wildlife-watch-china-orca-breeding-center-marine-park

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Corky_(orca

- https://www.nationalgeographic.com/animals/article/orcas-captivity-welfare

- https://www.wxxinews.org/npr-arts-life/2015-03-23/former-orca-trainer-for-seaworld-condemns-its-practices

- https://www.worldanimalprotection.us/latest/blogs/story-keiko-first-captive-orca-returned-wild/

- https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2024/oct/16/orca-killer-whale-extinction-study

- https://www.oregonlive.com/today/2015/11/orca_performing_tricks_in_show.html

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_captive_orcas