This first image is a Company painting depicting an official of the British East India Company, c. 1760. He’s relaxing surrounded by Indian servants with the signature English and British red coat.

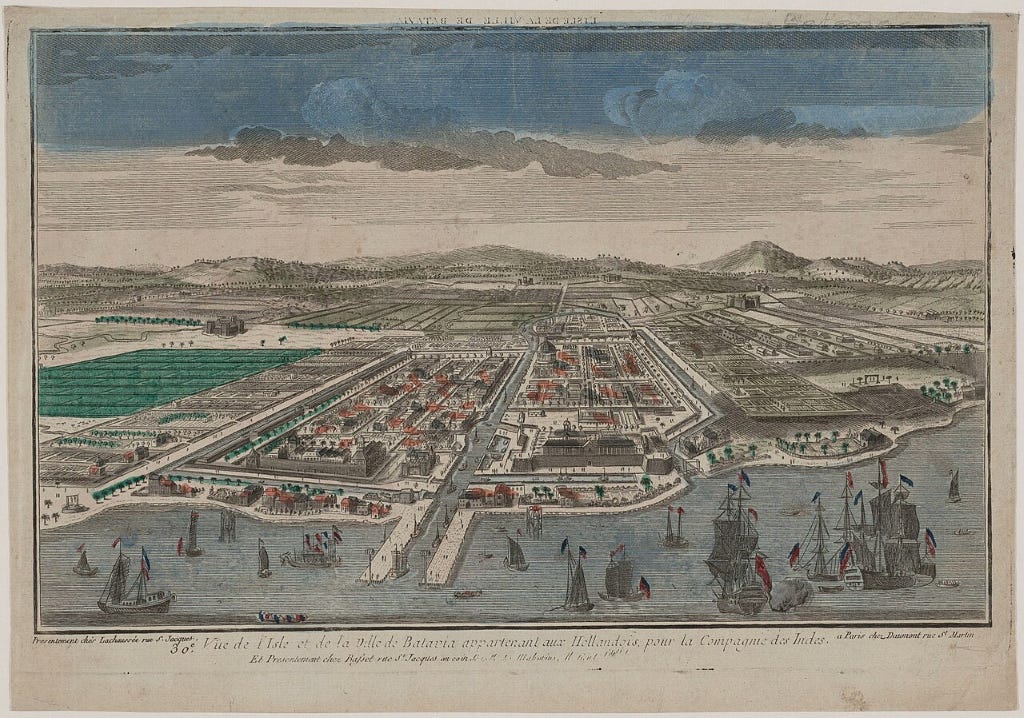

Here’s another one, a view of the Island and the City of Batavia (now Jakarta, Indonesia), belonging to the Dutch East India Company.

The Old World

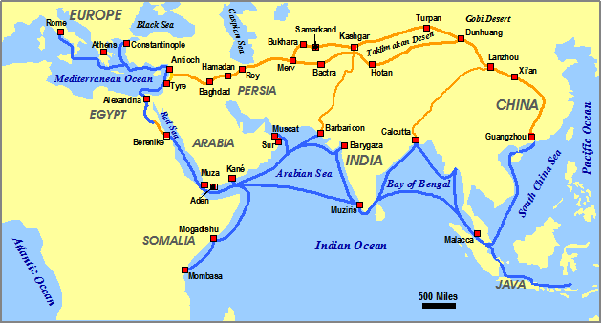

For centuries, trade to Europe from East, South, and Southeast Asia was through two simple routes. The first is the famous “Silk Road, “ a land route from China through Central Asia and Persia ending in the Mediterranean. The other is a sea route from the rich ports of the East through to East Africa and the Ottoman Empire before finally entering the European ports in Italy and the Balkans to be sold and distributed by the maritime trade republics of the Mediterranean, like Venice or Genoa. Through both routes, the spices, ivory, pottery, and silver would flow, generating enormous revenue and wealth for merchants.

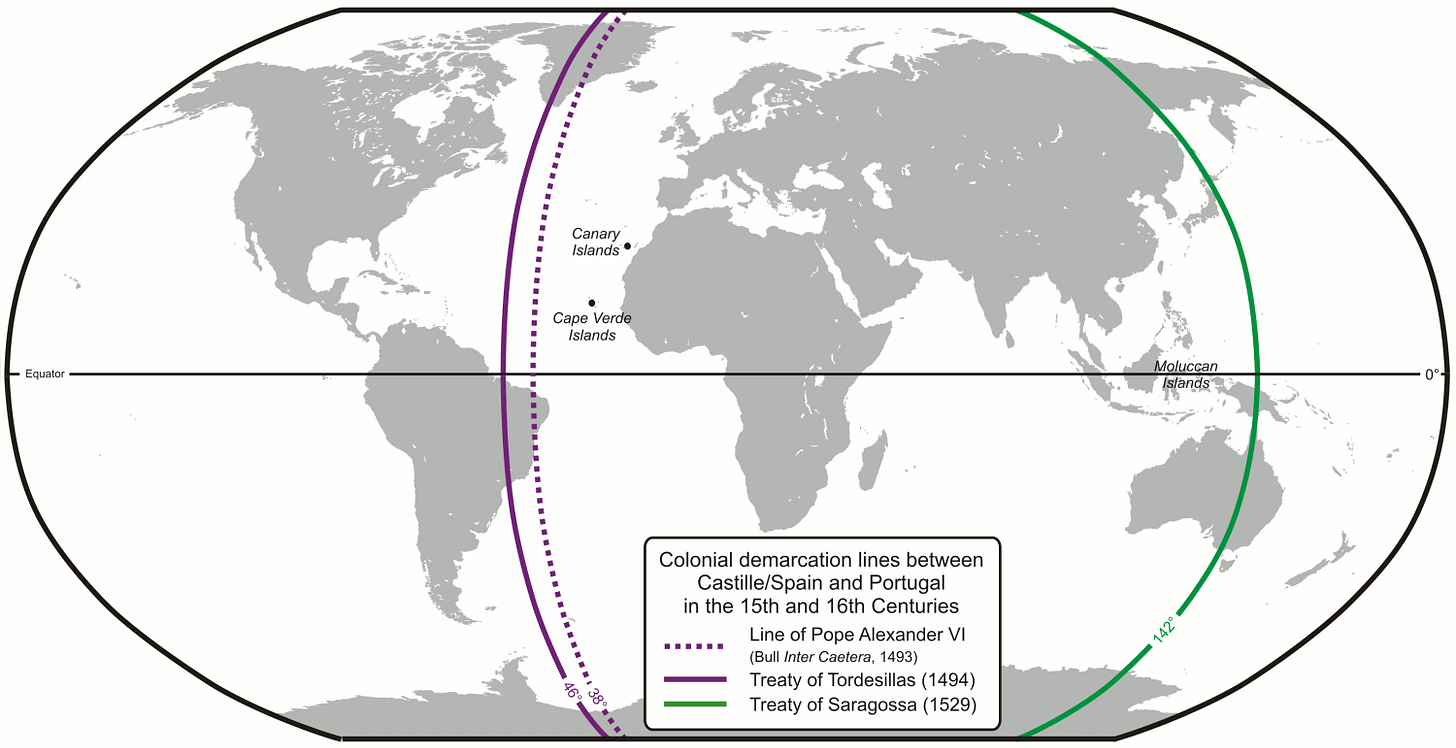

While empires and civilisations collapsed, this trade route remained the same since the time of the Roman Empire. But by the 1400s, there was a problem that faced the merchant classes and states of Europe. This route was expensive. The Ottoman Empire, which controlled the vital gateway of Egypt, the Levant, and the Sinai peninsula between the Indian Ocean and the Mediterranean sea, had imposed taxes on goods passing through its territories, leveraging its strategic position as a chokepoint on trade to hold a monopoly on all trade between East and West.

A new status quo

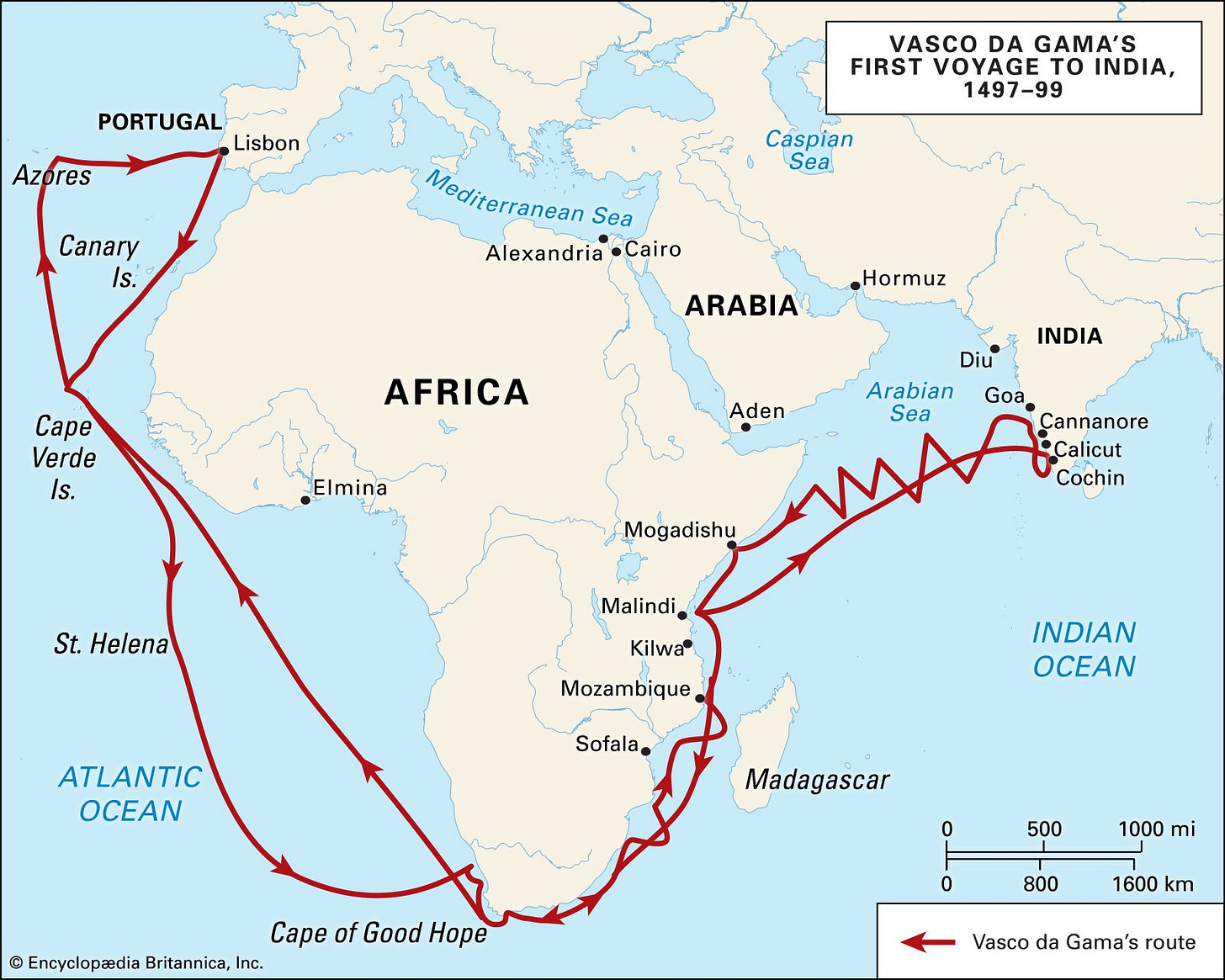

European explorers had long hoped for a direct route to India and the far east, one that did not require the expensive and tedious border crossing through the Middle East. They were, however, limited by the technology of their time, and as such, it was not until the 20th of May 1498, when Portuguese explorer Vasco da Gama set foot on the Indian continent for the first time, that a trade route from Europe to India by sea was discovered. He had sailed around the tip of Africa from Portugal, directly into India.

In the aftermath of his journey, maritime trade flourished, and the means by which Europe acquired the profitable goods from the East was no longer blocked by the Empires of the Middle East (though without a series of confrontations between the Ottoman Empire and Portugal). Ultimately, Portugal, one of the predominant maritime powers of the region, took control of the new direct route. In 1600, England began its chartered East Indian trade company to hold a monopoly over all English trade within the region, in hopes that it would bring riches to its shareholders, the state, and the crown. Two years later, the Dutch created the Vereenigde Oostindische Compagnie (VOC), their own East India Company, and over the next centuries, the French, Swedish, Danish, and other European states would follow.

For the next centuries after Vasco da Gama’s voyage, the only role and purpose of these newly formed Western trade companies was to generate as much profitable trade as possible. The companies formed “trading factories” led by factors and trading posts across the East Indies with the permission of local kingdoms and realms, to be used as ports to funnel goods to Europe and enrich the shareholders of these companies. The British set up their operations in Calcutta and the Portuguese in Goa. The Dutch did the same in Jakarta and the French in Pondicherry.

By the 1700s, such trading posts were common across the entire Indian subcontinent and Southeast Asia. They ranged in size, from the size of just a few buildings or a fort, to that of a large city, with trade extending all the way to the far east in China and Japan.

Christopher Columbus’s voyage West (originally to find a shorter route than Vasco De Gama’s to India) would also see the growth of not just these posts throughout the Western hemisphere, but full-scale colonial settlements and governorates across the continent. By this time, the traditional maritime powers of Spain and Portugal had gradually swept away, and were replaced by the new powers of Great Britain and France.

The New World

In 1754, a young Lieutenant Colonel by the name of George Washington ambushed a French force on the boundaries between French and British North America, beginning a 7-year-long global conflict across the world. Widely regarded as World War 0, the 7 Years’ War was fought on different continents, both in Europe and its colonies elsewhere. At the heart of this struggle were the East Indies companies of these Great powers, who found themselves battling each other militarily for control of various trading posts. Ultimately, in 1763, the French surrendered to the British, and the British East India Company would gain paramountcy over the entire Indian subcontinent, setting the stage for the transformation of not just the British East India Company but of all these trade companies away from profit forever.

The company painting depicting an official of the East India Company, c. 1760, shows a British East India Company official seated smoking with his Indian servants around him, drawn in the distinct “company” style which emerged from cooperation between British and Indian artists. The second image, on the other hand, shows a view of the Island and the City of Batavia (now Jakarta, Indonesia), belonging to the Dutch, for the India Company, the original trading post for the company. Together, they present the situation of the East in the 1760s in the aftermath of the 7 Years’ War, as companies moved to secure their country of origin’s areas of influence.

Distinctively, the first image presents the gradual integration of East India Company officials into greater Indian society, interacting with locals via settlement into its trading post cities and states. This would go on to create the identity of the “nabob,” the second sons of British nobles and aristocrats searching for their own fortune in the East through the company. These men of “new” wealth often integrated themselves into Indian society, taking part in their culture and customs, and often marrying Indian women, and when returning to England, presented competition towards the “Old wealth“. The first image presents the key cultural and social changes that came about in the aftermath of the 7 Years’ War and, more broadly, the growth of colonialism, in which men from trading companies found themselves increasingly integrated into the societies and areas in which they operated.

The second picture presents a different aspect of change, a change in the political and economic status of these trading posts. One of the key themes of trade companies post 1763 is, in addition to the integration of employees amongst the countries with which they trade, a movement away from profiteering towards empire-building. In 1757, Clive won the Battle of Plassey for Britain, annexing Bengal, India’s wealthiest province. The company found that taxation of annexed lands was becoming more profitable than selling goods from trading posts alone, and as a result, it began conquering lands to add to the company’s administration as a government. The Dutch in Batavia, as shown in the source, did the same, conquering the territories across modern-day Indonesia to use for the trade of spices, especially Cinnamon. The view of the city presents the key theme of empire-building and the creation of “indirect rule” brought on by the companies in the aftermath of the 7 Years’ War, which would intensify in the following years until these companies are eventually nationalised and their territories annexed into formal colonial empires in the early-mid 1800s, beginning “direct rule.”

By making use of both pictures, we begin to understand the situation in East and Southeast Asia, moving away from their role of trade and profit-making towards profit-making through war and empire-building. In the aftermath of these late 1700s changes, European powers would gain a secure foothold on the continent to continue expanding their colonial empires into the interior.

In the modern day…

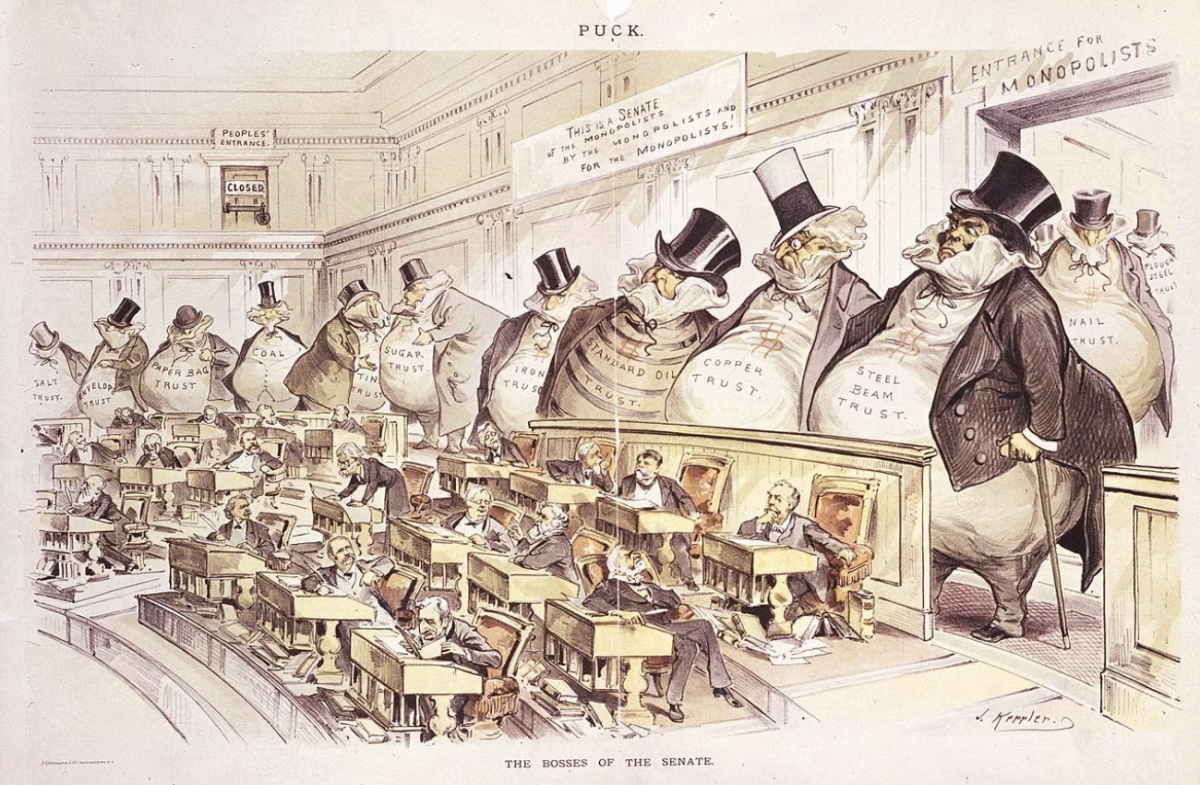

Some final considerations to make are that these companies were the first joint-stock companies. They sold shares to the public in a stock exchange, and directly preceded the system by which our stock market runs today.

The size and power of these corporations in the past can give us a viewing lens by which to see the influence of companies on trade and policy. In economics, the desire for revenue and profits, together with shareholder demands, drives and incentivises innovation. It is through these trade companies through the innovation of novel warfare tactics ushered in the Age of Colonialism.

We can certainly expect the same for our modern corporations, that their innovations are likely to generate new transformations that have and will affect global politics, the movement of people and migration, our culture, international relations, and, of course, trade.

References:

- Dip Chand (artist) – https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O16731/painting-portrait-of-east-india-company/, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=18728491

- https://digitalmapsoftheancientworld.com/digital-maps/trade/

- https://www.britannica.com/biography/Vasco-da-Gama

- Lencer – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=3194339