The recorder is often known as a “children’s instrument”, a false assumption that arises from the fact that it has had little to no interest invested in its development since the Baroque period – when most instruments had few or no keys and thus appeared simple in nature to the modern eye. Contrary to these contemporary beliefs, the recorder actually spent much time (from the 14th to mid-18th centuries) as a professional instrument that remained relevant until the transverse (typical) flute had gained enough sophistication and volume to replace it. However, a recent resurgence in the popularity of the instrument has led to the creation of new musical literature and instrument design specifications, which continue to develop and change with the needs of composers and instrument makers to this day.

It is likely that the reason why most players of the recorder nowadays were introduced to the instrument through school is simply that the lack of keys and small size was seen by music educators (as famous composer Carl Orff first saw it) as making it ‘easy’ to play. While the recorder, just like the xylophones that Orff also believed would revolutionise music education, is an easy instrument to start playing, mainly due to its simple fingering and easy embouchure (mouth positioning), becoming a professional player is very hard, not only due to the complexity that a lack of keys to facilitate chromatic playing but due to the limited range (or the complicated style of breath control, or the sheer lack of teachers of the instrument). This is similar to how, while the xylophone may look less daunting than the piano, the former is much harder due to the lack of an automatic mallet system, a lack which effectively prevents the player from performing difficult scales or chords!

This difficulty was once not so, as in earlier times, no wind instruments had many (or any) keys – or a large range – or a simple breathing pattern – or many teachers. This meant that the recorder’s only differentiating factor wasn’t that it was easy in many senses – or even that it was cheap (music was very expensive in those days) – but was the simple fact that the embouchure was less complex to learn than that of a flute and that less breath was required than for an instrument such as a crumhorn (curved early oboe with a windcap). This led to the ideal of femininity regarding the quiet instrument that contrasted the general idea of music being a male pursuit, a debate between traditional ideas of gender that lasted for much of the recorder’s heyday.

So, yes, there were some barriers to playing the recorder – but it remained popular. In the Renaissance period, which lasted until 1600, recorders were largely played in consorts with three or more ‘flutes’ (tuned in fifths, for example – with the lowest notes the F below middle C, middle C, and then the first G above that), although they existed from the sizes that would be known today as the many-keyed ‘contrabass’ up to the small and novel ‘garklein’. Recorders were used for the secular music of many social classes, although the sophisticated model of the consort was cultivated by the upper class – Henry VIII’s court was known to own over 70 recorders! They were also used for sacred music, especially to play renditions of polyphonic vocal works.

The recorder underwent further development in the early Baroque period. That is, during the early 1600s, a variety of more developed Renaissance recorders were created and enjoyed reasonable popularity in works such as L’Orfeo by Monteverdi, which contains parts for two sopranino recorders, likely in G. The true ‘Baroque’ model of the recorder, though, which is used as the standard recorder type even today, came later on; the unforeseen production of a seventeenth-century ‘flute’ changed both the design and the sound of the recorder to suit the music of composers such as Bach and Telemann, the latter of whom was known to play recorder to some degree and therefore composed a variety of works for it. The music of the Baroque period written for the recorder (or as it was known in England, ‘flute (douce)’ or ‘English flute’) avoided the consort setting that made up such a large part of the literature for the Renaissance ‘recordour’, instead using a ‘concerto’ (solo with orchestra), ‘sonata’ (solo with continuo or a multi-instrument bass line), or Baroque orchestral format. (Some solo work from the era also exists for the instrument, but it is not particularly popular.) Each of these musical structures developed over time to create a large repertoire that contains many of the best works for recorder – an example being Vivaldi’s incredibly difficult yet beautiful Concerto per Flautino in C Major, which is played to this day.

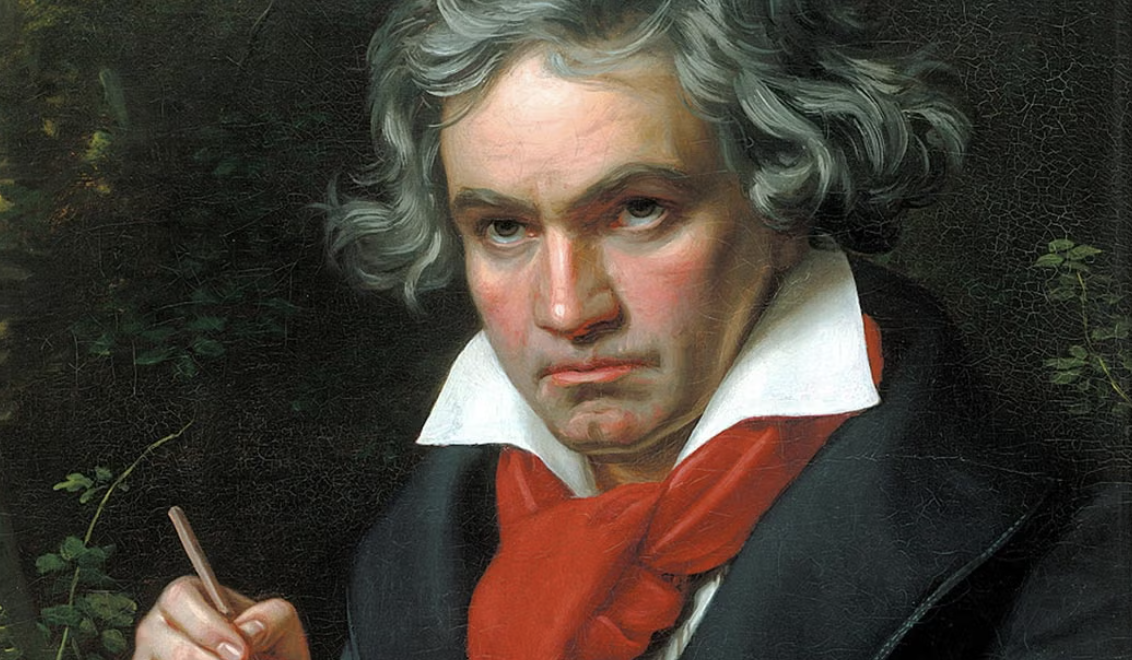

The ’German flute’, transverse flute, or simply ‘flute’ had existed for as long as the recorder. However, it only overtook the recorder in popularity in the late Baroque period, leading to many years of the former being largely redundant. Some recorder-like instruments coexisted with the flute, although these were less popular: in the late 18th and most of the 19th centuries, especially among the middle- and upper classes of French society, the French flageolet emerged to the public eye, enjoying a reasonable repertoire and good popularity – although after an incredible series of developments that involved the addition of complex keywork to the instrument, it began to wane in popularity, becoming almost unheard of by after World War I. Additionally, ‘English’ flageolets and the czakan became popular, played by such famous men as Robert Louis Stevenson and Beethoven – although a similar decline was seen in their popularity eventually. All three kinds of flageolet functioned in the same way as the recorder – effectively like a whistle using a ‘duct’ or ‘fipple’ system – but in due course the two ‘true’ flageolets developed a ‘beak’, or decorative cap, which lent them an appearance similar to an oboe. Meanwhile, many czakans were styled to look like a walking stick – none are played today to a great degree.

Despite this sad decrease in the amount to which these instruments were played, a resurgence in popularity of the original recorder by the 20th century led to a variety of new, experimental compositions – such as by the two greats of twelve-tone composition, Schoenberg and Hindemith. Works with new levels of complexity were performed on instruments adapted to suit the modern day, while purists such as Dolmetsch created periodically accurate instruments, and music educators researched the plausibility of using plastic and other materials to cheapen the production of an instrument that was traditionally made of pricey hardwood or even ivory. All this good work was somewhat reversed by the later stereotyping of the recorder as an ‘easy’ or ‘useless’ instrument, but with the Internet and an increase in the global population the recorder is actually more popular than ever!

I myself initially played the recorder as a tool for music education, but my natural curiosity and a few searches of the Internet and of my mother’s selections of sheet music led me to discover a wealth of original tunes that I played both on my own and in groups. I stopped in favour of the flute, having already begun work on the piano and violin, but have continued recently after acquiring a variety of modern reproductions of Baroque instruments in pearwood or maple. Today, I play a variety of difficulties and styles of recorder music, but have no teacher and no acquaintances who play the recorder – leading to my interest in telling more people about this incredible instrument, with the aim of inspiring a future generation to play it!

I hope that you are interested in playing it too, or even participating in a recorder group with me, provided you live in the Auckland/North Waikato regions of New Zealand.

Thank you for reading my article. If you have any questions regarding the instrument, please email or DM me.

CGAPressObserver • May 20, 2024 at 11:10 am

Great article