French, Mandarin or … Python?

“As technology helps the world become more interconnected, our ability to understand and work with others on technical projects around the globe is not only related to the ability to code, but to understand one another.” – Padma Kuppa (mechanical engineer and member of the Michigan House of Representatives)

Coding has rapidly developed into one of the most important skills of the 21st century, and one that many educational facilities have begun teaching to primary and high school students due to its highly sought-after nature within the modern workplace. Over the last decade, however, learning to code has been frequently compared to learning a foreign language – a misconception that could have major consequences for world languages and communication in general.

In the USA, some states (such as Florida and Michigan) have attempted to pass state legislation that would allow high school students to fulfil foreign language requirements through coding in programming languages such as Python and JavaScript, with proposals stemming back as early as 2014. Whilst the implementation of coding into school curriculums has been an area of debate in and of itself, especially when introducing it at a primary school level, the suggestion that coding is an equivalent to a foreign language is inherently flawed, both in terms of their different functions within society, and in the cognitive processes that they rely on to be understood.

Firstly, it is important to highlight the major differences between programming languages (considered to be constructed languages) and our everyday form of language (termed natural language). The Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary defines a natural language as: “a language that is the native speech of a people (as English, Tamil, Samoan),” or “the language of ordinary speaking and writing.” The Collins Online dictionary further defines it as: “a language that has evolved naturally as a means of communication among people.” In essence, this makes the combined definition of a natural language: ‘a language of ordinary speaking and writing that has evolved naturally as the native speech and means of communication among people’. In contrast to this, the Collins dictionary defines a constructed language as: “a language whose rules and vocabulary have been artificially invented”; and a programming language as: “a simple language system designed to facilitate the writing of computer programs.”

When these definitions are considered, the fundamental difference between a natural language, such as English, French or Mandarin, and a programming language like Python becomes clear: their function within society is entirely distinct. A natural language is used as a means of communication between people, and can convey complex thoughts and emotions alongside the history and culture of a certain group, whilst a programming language’s primary function, although having to be understood universally by programmers, is to create a command that can be processed and executed by a computer.

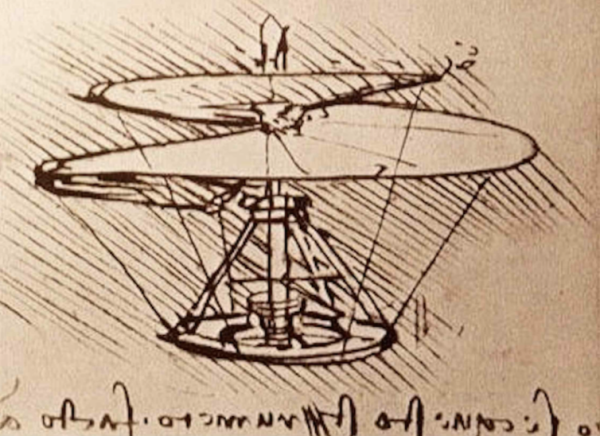

Despite this, it is important to outline that there are some inherent similarities between a programming and natural language. An example of this lies in the fact that both rely on a series of symbols and specific syntax – a fact which has created the assumption that both natural and programming languages rely on the language-processing centres of the brain. However, research published in 2020 by neuroscientists from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) has revealed that the human brain does not process computer code in the same way as it does a language. In fact, using programming languages does not rely on the language-processing centres of the brain at all – outlining the major issue with viewing this as performing the same educational function as learning a foreign language.

Evidently, whilst coding has undoubtedly become a vital skill to possess within the 21st century, its importance should not be exaggerated, as it still performs the primary function of a tool, rather than a complex, cultural and historical language. In the words of French philosopher, Gaston Bachelard, “A special kind of beauty exists which is born in language, of language, and for language,” – a beauty that is unique to human nature and communication.