Signs are to Eyes what Words are to Ears

“Signs are to eyes what words are to ears.” – Ken Glickman

As one of the cornerstones of individual and cultural identity, language’s ability to convey the history, beliefs and ideas of a person or community undoubtedly highlights why it continues to play such an important role in our day-to-day lives. From writing emails or text messages to speaking with teachers or friends, language is vital in enabling communication between individuals. However, the true scope of language extends far beyond its written and verbal forms, with hand gestures and other aspects of body language playing equally vital roles in the type of communication used by sign languages.

Whilst there have historically been conflicting perspectives surrounding the ability of such sign-based, non-verbal forms of communication to classify as ‘real’ languages, their natural development by individuals and communities with hearing loss, reliance on set grammatical and syntactic structures and distinct vocabularies clearly conform to Merriam-Webster’s definition of a natural language, namely: “a language that is the native speech of a people”. In fact, with over 300 different sign languages across the globe, including American Sign Language (ASL), Auslan (the sign language used in Australia), French Sign Language (FSL), British Sign Language (BSL) and Hong Kong Sign Language (HKSL), the United Nations has declared the 23rd of September as the annual International Day of Sign Languages.

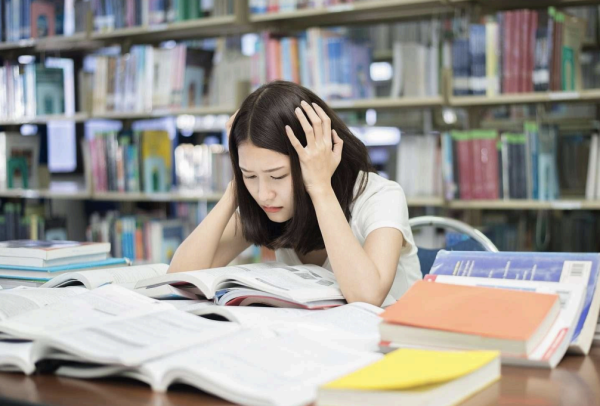

Despite such positive developments in their international recognition, however, the general understanding and appreciation of these languages is a relatively recent feat. Whilst various types of hand gestures have been used for centuries as a form of silent communication for hunting (such as by the San people and the Great Plains Native Indians) or during monastic rituals, the development of formal sign languages for the purposes of communication between individuals with hearing loss only truly began in the 1500s.

It was during this time that a Spanish Benedictine monk, Pedro Ponce de León, began teaching such individuals how to speak and write, as well as to use hand gestures. This was a major milestone in the recognition of the need to educate individuals with hearing loss, especially considering the fact that these individuals had previously been viewed as ‘inferior’ to other members of society, and had been labeled as “deaf and dumb” as a result of their lack of access to education. However, it was over two centuries later, in 1760, that the first formal educational institute for individuals with hearing loss was established by Charles-Michel de l’Épée. This institute, which was located in France, helped to formalise the existing hand gestures being used by individuals with hearing loss in the region, thereby developing the origins of the standardised French Sign Language.

Similarly, the first school that focused on teaching sign language to individuals with hearing loss was founded in the early 1700s in America by Thomas Hopkins Gallaudet. By adapting the existing system of sign language used in France, and by incorporating the hand gestures used by local groups, this institute was able to formalise and standardise American Sign

Language, which has in turn influenced the development of a number of other such languages around the world.

An example of this is South African Sign Language (SASL), which draws not only from the gestures and signs used by languages such as ASL, but also from local varieties or ‘dialects’ of sign language, including the system used by the San people. With its own unique structure and distinctive style, SASL is joining the group of sign languages that have been recognised as official national languages across the globe.

Once its addition has been formalised, SASL will become the thirteenth official language of South Africa, and highlights the growing recognition of such forms of communication and their respective communities. After all, as the British novelist Angela Carter once stated, “Language is power, life and the instrument of culture, the instrument of domination and liberation.”

Sources:

- https://www.un.org/en/observances/sign-languages-day

- https://www.academyhearing.ca/blog/news/News/2016/11/16/50:the-fascinating-history-of-si gn-language

- https://www.westerncape.gov.za/as sets/departments/cultural-affairs-sport/national_institute_for_the_deaf_sa_sign_language_b ooklet.pdf&ved=2ahUKEwjCuLm4muv4AhWAuZUCHS1oDLQQFnoECCkQAQ&usg=AOvVa w3npTD2rL_HD3WqLrgkHUVX